The end of the modern culture is one of those things that most people can see coming but few want to acknowledge. Our culture’s ending is guaranteed by college educated populations failing to reproduce at rates sufficient to sustain the population. In the end, this failure means that modern culture must end, unless it can sustain itself parasitically on a non modern culture that is fecund enough to both sustain itself and the burden of a modern culture. But based on all available evidence, modern culture is very successful at supplanting whatever traditional culture it comes across if given a level playing field. For this reason, it seems unlikely that modern culture will ever be able to moderate its own success in a manner that would enable it to be successfully parasitical.

Granted, that message of doom and gloom is not mainstream. But it is the only conclusion supported by simple math and observing what is going on around us in the world. Anyone who is capable of understanding basic logic and is aware of the world around them should be able to understand it for themselves. At least, that is what I would like to think.

In reality, it is apparent the people struggle mightily with basic logic and they are not at all keen on observing the world around them. This has recently been rubbed into my face by the reaction to Tyler Cowen’s recent musings about how the world might “stop depopulating.” Cowen’s musing are banal and even a little delusional. But at least his musings acknowledged the basic mathematical fact that this has to stop at some point or the human race will cease to exist. Nonetheless, his comment section was overrun by people mocking or otherwise uncomprehending why Professor Cowen thought “depopulating” was a problem. Apparently, simple math is a form of logic too deep and complicated for most of his readership to comprehend.

One point that was repeatedly made in the comment section particularly got under my skin and is the occasion for tonight’s rant. And that is the idea that people have been predicting for a long time that demographic issues were going lead to an economic catastrophe for Japan and yet Japan is still going strong. I have seen this argument advanced many times over the last few years and yet rarely do I see anyone explain why this is logically and observationally an absurd argument.

To rectify that, I thought I would throw together a brief explanation of why the idea that “Japan shows the demographic decline is not a problem” is absurd.

First, let us start off with couple of things that everyone should be able to agree with. For starters, let us make the observation that country’s economic strength consist entirely the people in the work force and their productivity. Some people might try to throw natural resources in there as well, but really this is already accounted for in productivity. A farmer on good land will be more productive then a farmer on bad land just as a farmer with tractors will be more productive then farmers with hoes. And people with easily accessible oil will be more productive in the energy business then those who don’t.

Now there are a couple of points that we can derive from the above point. The first one is that if you increase productivity faster than the population falls, you can hold economic strength steady or even increase it even as your population falls. Obviously this has its limits because if the population is zero, then there is no productivity. But nonetheless, falling population and economic growth are not necessarily mutually exclusive in theory.

The other point we can derive from the above is that in modern economies that make little use of child labor, children contribute nothing to economic strength in the short run. In fact, they are nothing but a burden because they are not part of the work force and yet resources have to be found to feed, house, and educate the little brats.

So keeping those two things in mind, what would the impact be on economic strength if after today; no more children were born in an advanced economy that did not allow immigration? The answer is that in the short run there would be no impact because it would not immediately impact the amount of workers in the economy. In fact, it might even be beneficial as the money normally spent on children could be used to boost productivity via investment in capital equipment. It would take twenty years from the day all childbirths stopped for the work force to even start feeling the pinch because up until that time there would still be children “in the pipeline” who would be entering the work force. Even then, it would not be immediately devastating but with each passing year things would get more and more desperate as the economy would not be able to make up the workers that it lost each year to death and infirmity. As a rough rule of thumb, we could say it would take twenty years for the economic impact of no new births to be felt and thirty years for it to get real bad.

There are two points from this little thought experiment that we should always keep in mind. The first is that in the short term, not having children is beneficial (or at least not harmful) to a modern economy. Yes, fewer children might hurt industries geared around children such as daycare or toy makers, but it will benefit other industries such as cruise lines and sports car makers that are otherwise negatively impacted by people having children. The second point is that even if a catastrophic demographic crisis is facing a nation (as surly we can all admit that having no children at all would be) it will still take awhile before it starts impacting the nation economically. And even in the case of having no children at all, the bad effects will take time to show in the GDP figures.

With those points of logic out of the way, let us take a look at the real world case of Japan. Let us start off with a couple of key dates……

1952— This is the first year that Japan’s fertility rate dropped below 3 and never went back above it. Before 1952, there is not a year on record where it was lower than 3. After 1952, it never hit 3 again.

1975— This is the first year that Japan’s fertility rate dropped below 2 and never went back above it. The fertility rate occasional dropped below this number before that but that was more along the lines of natural variations. After 1975, it would never even come close to 2 again.

1994—– In this year, Japan’s fertility rate dropped below 1.5 never to rise above it again (although it did get up to 1.45 in 2015 only to start dropping back again.

2005— This is the first time in Japan’s modern history that its population started going down. Before this you have to go all the way back to 1945 to see a year in which Japan’s population dropped. Outside of 1945, there is no other year going all the way back to 1899 that Japan’s population dropped. And prior to 1899, I don’t have access to any data. (Incidentally, it is kind of amazing to me that out of all the years that Japan was involved in World War II 1945 was the only year that the population dropped. All the rest of the war years Japan had double digit population growth. One thing this shows is that demographically speaking, Japan could have sustained the war for a long time as long as they could have kept the war away from their homeland.)

2010— After this year, the loss of population was 1% a year and growing.

2020— Loss of population (which has been ongoing right along) reached an annual rate of about 4% a year and I imagine the number will keeping going up with some variation from year to year. By way of comparison, the year (1945) that Japan was nuked and firebombed and every other disaster you can think off only saw a population drop of roughly 6%.

One thing that is interesting to note is that fertility seems to reset (if it is going to do so), on a generational basis. After 1952, it never again went above 3 (prior to that was it was the norm to go above 3). After 1975, it never again went above 2 (and prior to that it was the norm to go above 2). After 1994 it never went above 1.5 when prior to that it was normal for it to be above 1.5. As you can see, there is roughly 20 years between those numbers and to my mind that indicates a generational change. Obviously this is not a fixed law, because current generation of Japanese seems to be holding a fertility rate at the same rate as the previous generation.

So what has been the economic impact of this lack of children? Let us look at the below GDP chart…..

Japan GDP Growth Rate 1961-2021. www.macrotrends.net. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

The bottom row of bars just shows how much economic growth changes year over year. It does not pertain much to our argument except to note that economic growth (or lack therefore) has been pretty constant in modern Japan.

What is more germane to our argument is the 20 year pattern in the GDP data. Starting in the 70s economic growth was on average less than it had been in the 60s. Starting in the 90s in the economic growth was in lower than in the 80s. And starting in around 2010, the economic growth is at an even lower plateau then it was previously.

This is just what our thought experiment would lead us to expect. The 1970s are 20 years out from when the first drop in Japan’s average fertility started in the 1950s (although we should not forget that some of the wild economic swings in the 70s were caused by the oil embargo). The 1990s are 20 years out from when the second drop in Japan’s average fertility started in the 1970s. And 2010 is 20 years out from when the last drop in Japan’s average fertility started in the 1990s. And we should not be surprised that the GDP growth drop starting in 2010 is not that dramatic because the change in going from below 2 to below 1.5 was not as great as a drop as earlier changes.

Now I am old enough to remember that if you have predicted Japan’s current economic performance in the 1980s you would have been considered delusional. At the time the argument was between those who thought Japan might overtake America’s economic strength and those who thought that was not really possible. No one I am aware of predicated that Japan would become a sluggish and anemic economic power. Even in the 1990s people thought they could return economic growth in Japan to “normal”.

These days pretty much everyone accepts that Japan will never go back to being a high growth economy because of demographic reasons. The arguments have of Japan’s optimists have changed from “Japan will overtake the US” to “Demographic decline is no big deal because Japan still has some economic growth even if it is minimal.” But this is as hopelessly optimistic as the idea that Japan was poised to overtake American as the world’s leading economic power.

The reason this optimism is as “hopeless” as the optimism of the 80s is that it ignores the fact that Japan has been making up for its labor shortfalls by pulling more woman into the work forces. And that trick is about all used up.

To understand why this is trick is about to end, let us go back our thought experiment about a country that stopped having children altogether. Let us imagine that up to the point that it stopped having children, the female participation rate in the work force was low. Let us say that after they stopped having children the woman started entering the work force in ever greater numbers. It is possible that at the 20 year mark from when the country stopped having children, there would be no drop in the work force because the increasing participation of females in the work force would balance out the lack children reaching adulthood. Now how long could this balancing out of effect last?

The obvious answer is that it depends on a number of factors, but the absolute limit of this balancing out effect will be reached when the female participation in the workforce reaches 100%. At that point, an economy that has stopped having children will still be experiencing labor short falls as the older workers die off and no new children are reaching adulthood but there will no longer be any unemployed females to pull into to the labor force to make up the difference.

With all that in mind let us look at some charts showing female participation in Japan’s workplace. The chart below looks at females as a share of the labor force.

Roughly speaking, when female share of the labor force goes to 50% there are no more females to pull into the labor force (although it is theoretically possible that it could go a little higher than 50%). Also, a lot of woman in Japan work at part time jobs that could be translated into full time employment. But there is no mathematical way that line keeps going up the way it has in the past because they are already at 45%.

As we can see from these charts, Japan is nearing the end (and may in fact be at the end) of its ability to draw more females into the workforce to make up for its demographic shortfalls. If you understand that Japan’s current low rates of economic growth have only happened because there was a rapid rise in female employment you can see why the optimistic case for Japan’s future has no merit.

And this future is even worse when you fully think through the implications of what we have just talked about. For example, let us say that Japan’s females decided to return to a fertility rate high enough to sustain Japan’s current population (2.1). The immediate impact will be negative for the economy because it now depends on 100% female participation and there is no country in the world where woman getting pregnant and having small children does not impact their labor participation rate. In the short term woman having more children will increase the labor shortages and exasperate the economic pain from Japan’s already baked in demographic short falls.

And this is what makes demographic problems an existential threat to any culture with a short term view on life and whose life choices are dictated on economic criteria (which basically describes all humans). In the short term there is nothing but economic benefits from not having children. In the medium term, the lack of new adults starts to bite but there is often ways alleviate these problems. In the long term, the lack of children is absolutely deadly to a culture. At any point along this process it is biologically possible to return to replacement levels of fertility but the further along countries go in this process the more economically painful it becomes to return to having children. For this reason, countries that are already economically struggling (as most countries experiencing demographic decline are) are the ones hardest pressed to raise their fertility rate.

What can possibly rescue a nation from this intractable fate? Some people like to think that productivity (often couched in terms of robots or other technological marvels) will provide a painless way out of this trap. As we noted at the start of this rant, in theory this is possible. But in practice this is not a hope that is supported by Japan’s history as the below graph shows.

What the above graph shows, is how long it took to get to the productivity level of 2017. As the above graph shows, most of the rise in Japan’s productivity happened before 1970. After that, productivity growth in Japan slowed to a crawl outside a brief surge in the late 80s. Now Japan has been particularly bad a growing productivity compared to the US in recent years. But even if we imagine that Japan is about to experience productivity growth that the US did at its peak of productivity growth (1913 to 1950) its productivity growth would only be 2.5% max. Even that extremely unlikely productivity growth rate is not going to make up for a 4% or more drop in the workforce every year.

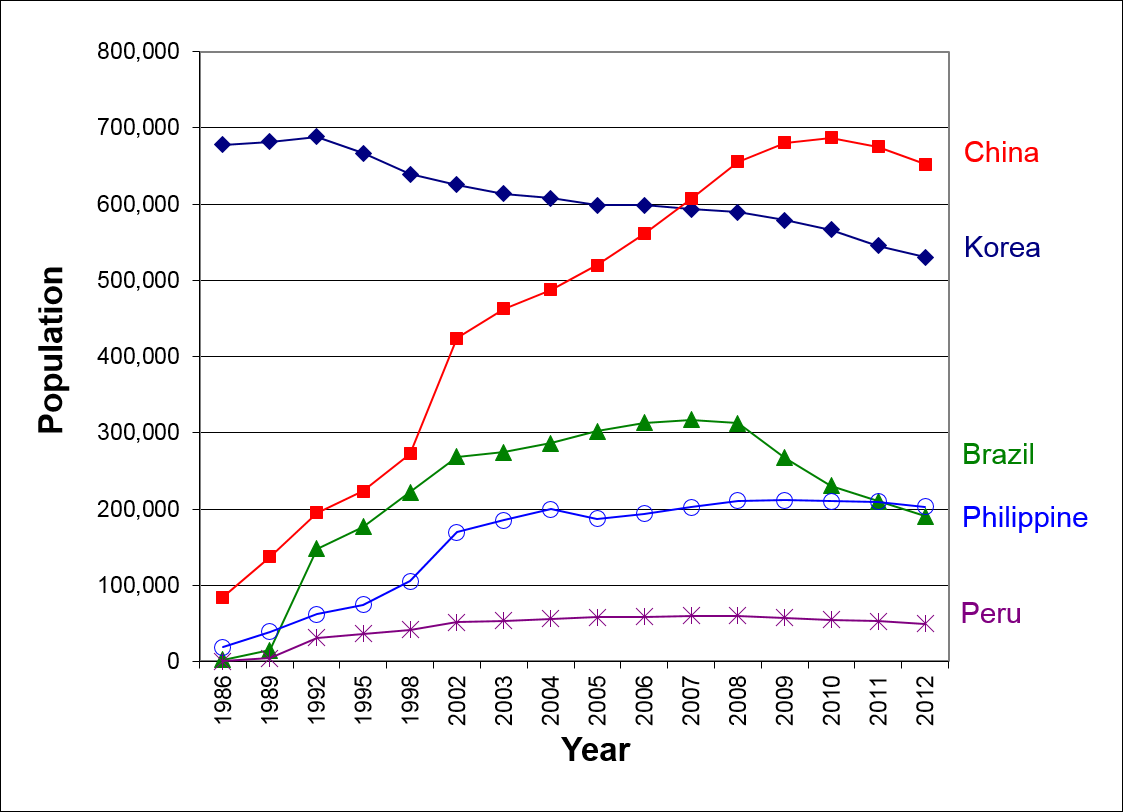

A more realistic but still not likely solution is that Japan will have to start allowing in more immigrants. And Japan has made half hearted attempts at this (see below chart).

Given that Japan’s population is still greater than 100 million, the numbers shown on the above chart are just a drop in the bucket and after a period of growth most of the trends are headed the wrong way from a demographic perspective. Moreover, Japan is going to face ever increasing competition attracting the type of immigrants that they want (primarily educated ones that somebody else has paid to educate).

The long and the short of this is that immigration is unlikely to rescues Japan. Even in the unlikely event that Japan does become a prime destination for immigrants it will only provided short term relief. In the long term, it will not change the long term trajectory of modern demographic collapse that Japan is caught up in. More and more countries are heading the same way as Japan. Even those countries that are still over 2 are dropping like a rock. They will all find it just as difficult as Japan to reverse the situation.

The bottom line is that people who are optimistic about Japan based on the fact that its recent economic doldrums are “not that bad” are ignoring how the economic effects of demographic changes always have a lag in them. They have failed to notice that Japan’s ability to offset demographic shortfalls by increasing female labor rate participation is about to end. And lastly and most importantly, they offer no credible way for Japan to stop this demographic slide that mathematically will end Japan as a nation if it is allowed to go on long enough.